Sighthound Anaesthesia Focus: Hepatic Considerations

Anaesthetising sighthounds has always required a slightly different lens. Their unmistakable physiology—lean bodies, low body fat, and unique metabolic quirks—means they don’t always play by the same rules as other canine patients. While much of the clinical conversation centres around their sensitivity to certain anaesthetic agents, one area that deserves equal attention is the liver.

Sighthounds possess hepatic differences that can significantly influence drug metabolism, anaesthetic recovery, and peri-operative risk. Understanding how their livers process (or struggle to process) commonly used agents isn’t just academically interesting—it’s essential for achieving safe, smooth, and predictable anaesthetic outcomes.

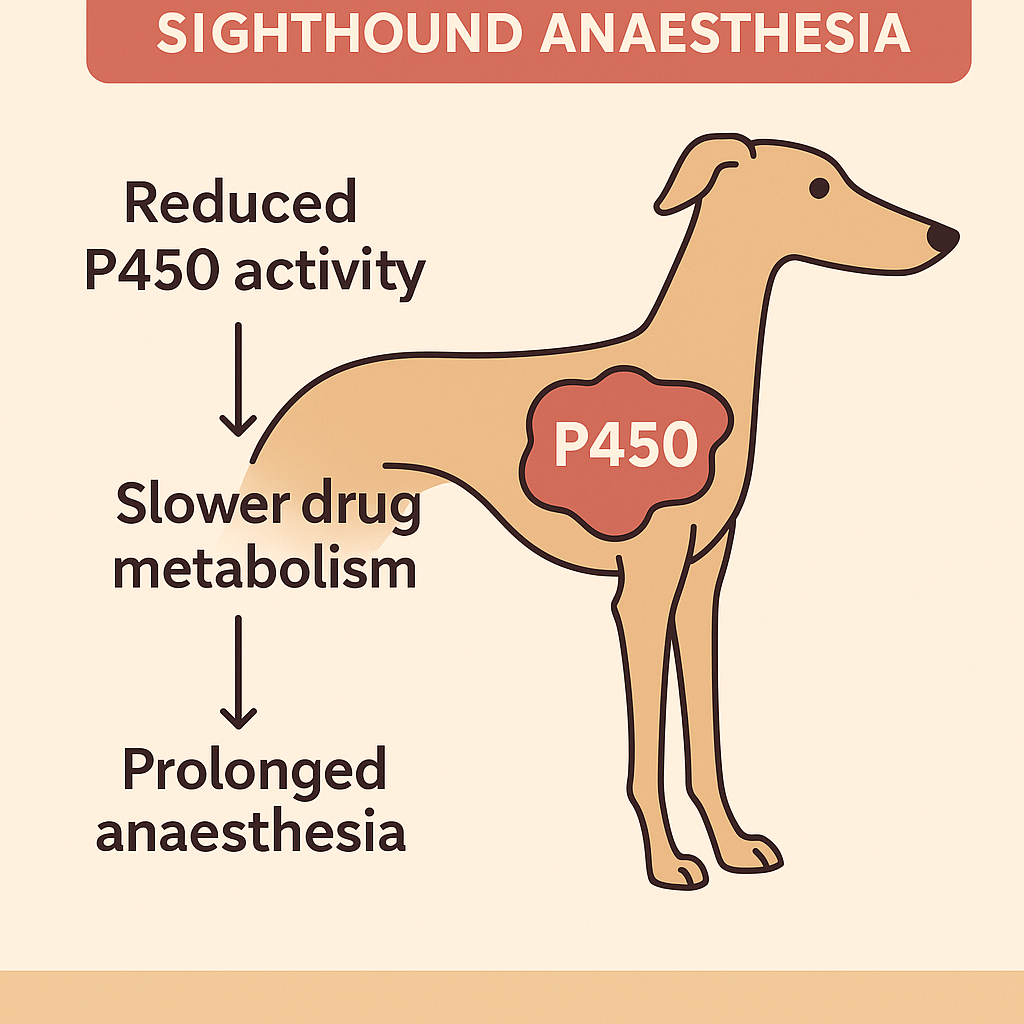

Cytochrome P450

Cytochrome P450 is a superfamily of enzymes responsible for oxidising (chemically modifying) drugs, toxins, and some endogenous compounds so the body can break them down and eliminate them.

Think of CYP450 enzymes as the liver’s chemical processing machinery—each type specialises in breaking down certain drugs.

Where Are They Found?

-

Mainly in the liver, but also in the GI tract, lungs, kidneys, and brain.

-

In hepatocytes, they are located in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum.

What Do They Do?

Cytochrome P450 enzymes carry out Phase I metabolism, which usually involves: Oxidation, Reduction and Hydrolysis.

Why Do They Matter?

Different CYP450 enzymes metabolise different drugs.

For example:

-

CYP2B11 helps metabolise thiopental, propofol, and some other anaesthetics.

-

CYP1A2 helps metabolise lidocaine, diazepam, certain NSAIDs.

-

CYP3A12 handles many opioids, sedatives, and other common agents.

If a breed has low activity or mutations in a particular CYP enzyme, it may metabolise that drug more slowly or unpredictably.

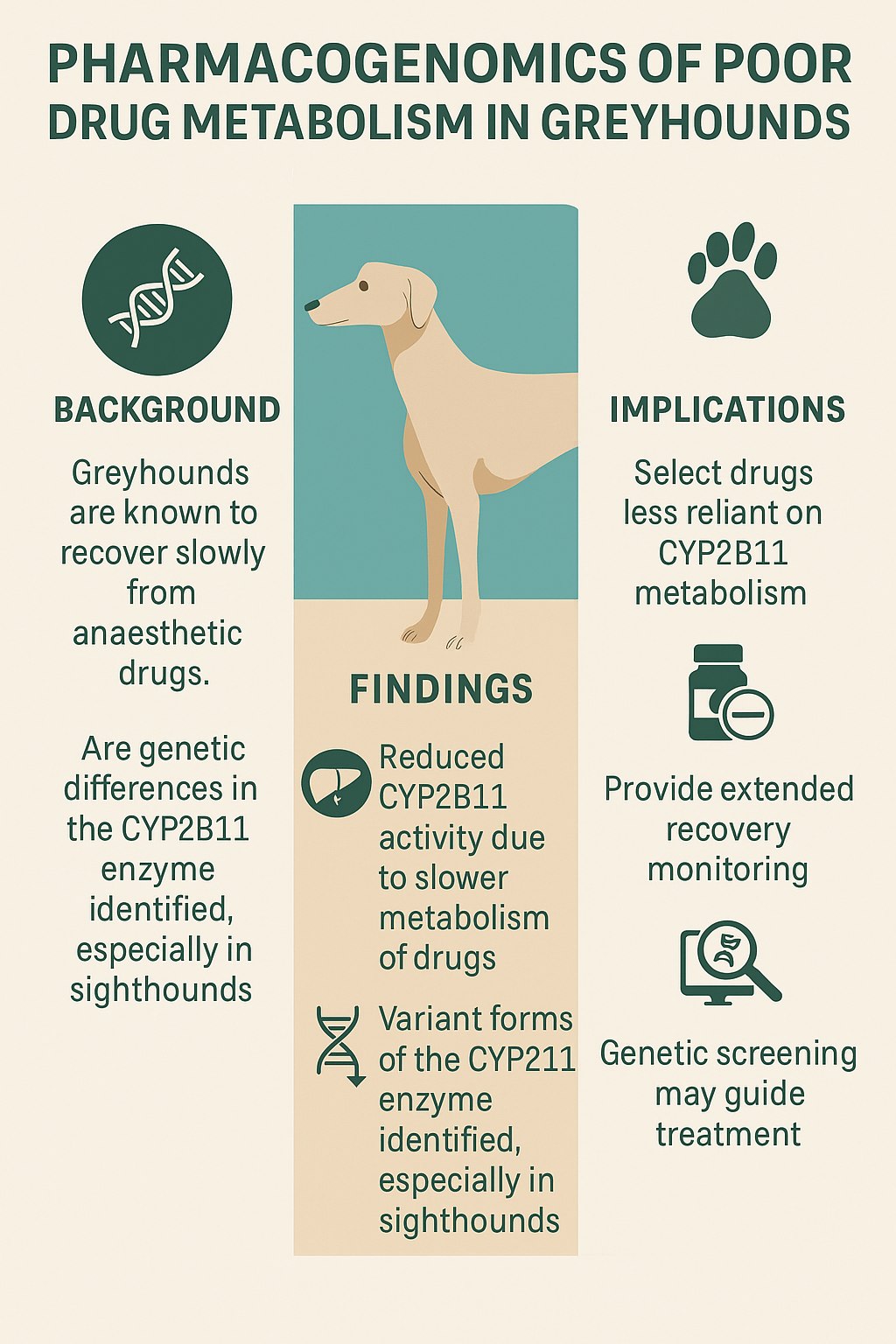

What We Know About Sighthound Changes In The P450 Enzyme

One of the most clinically significant features of sighthound anaesthesia is the way these breeds metabolise drugs at the hepatic level. Much of this can be traced back to differences within the cytochrome P450 enzyme family, particularly CYP2B11, CYP1A2, and CYP3A12. These variations help explain why certain anaesthetic agents behave so differently in sighthounds compared with other canine breeds.

In Greyhounds—and to a lesser extent in other sighthound breeds—there is a well-documented reduction in the expression and functional activity of CYP2B11, the canine equivalent of human CYP2B6. This enzyme is responsible for metabolising several commonly used anaesthetic and sedative agents. Because CYP2B11 is underactive in these dogs, drugs that depend heavily on this pathway are broken down far more slowly.

The practical consequence is usually prolonged recovery times, most famously associated with thiobarbiturates such as thiopental. Before more modern induction agents became mainstream, Greyhounds were known for taking hours—sometimes even days—to recover from what would be routine doses in other breeds. Even today, this reduced metabolic capacity can lead to exaggerated effects or slowed clearance of certain lipophilic anaesthetic drugs, especially when higher doses or repeated boluses are used.

Altered CYP1A2 Activity

CYP1A2 activity in sighthounds is more variable but still clinically relevant. Some lines appear to have lower baseline CYP1A2 activity, a trait that may be influenced by both genetics and environmental factors. Because CYP1A2 plays an important role in the metabolism of drugs such as lidocaine, diazepam, and specific NSAIDs, differences in its activity may contribute to variations in sensitivity or duration of effect. While not as dramatically impactful as the CYP2B11 deficiency, it remains an important consideration when selecting sedatives, analgesics, and adjunctive medications.

So What Matters Here?

Greater Sensitivity to Lipophillic Agents

Another key factor that influences anaesthetic outcomes in sighthounds is their extremely low level of body fat. In most dog breeds, lipophilic (fat-soluble) anaesthetic agents distribute quickly from the bloodstream into adipose tissue. This redistribution acts as a temporary buffer—effectively a storage site—allowing plasma concentrations of the drug to fall even before the liver fully metabolises it. In sighthounds, this mechanism simply isn’t available. With so little adipose tissue to absorb these drugs, the full circulating dose remains within the bloodstream and central nervous system, prolonging and intensifying the anaesthetic effect.

When this naturally limited redistribution is combined with the already reduced activity of CYP2B11 and other metabolic enzymes, the pharmacokinetic challenge becomes even greater. Lipophilic drugs stay in circulation longer, and the liver struggles to clear them at an appropriate rate. As a result, sighthounds are more likely to experience deeper-than-expected anaesthesia from standard doses, along with extended recovery times as their bodies slowly work to metabolise and eliminate the agent. This creates a narrow therapeutic margin where an ordinary dose in another breed could be excessive or produce prolonged sedation in a sighthound.

This phenomenon is one of the reasons that thiobarbiturates historically posed such problems for Greyhounds. These drugs are highly lipophilic, meaning they rely heavily on both adipose redistribution and efficient hepatic metabolism—two processes that do not function typically in sighthounds. Without either of these pathways operating effectively, the drug remains active far longer than intended.

Alfaxan Suggested…

Alfaxan avoids many of these issues, making it a safer and more predictable induction agent for sighthounds. Unlike thiobarbiturates or agents that are heavily reliant on CYP2B11/P450 metabolism, alfaxalone undergoes rapid redistribution and is primarily cleared via pathways that remain intact in sighthound breeds. It is less dependent on the specific cytochrome P450 enzymes known to be reduced in Greyhounds, meaning its clearance is not significantly compromised by their unique metabolic profile.

Additionally, although alfaxalone is lipophilic, it behaves differently from classic fat-soluble anaesthetics because of its formulation and pharmacokinetics. Alfaxan allows for fast onset and rapid decline in plasma concentration, even in dogs with low body fat. Redistribution occurs efficiently despite limited adipose stores, and hepatic clearance is faster and more consistent than with drugs like propofol or thiopental. As a result, sighthounds typically experience smooth inductions and predictable recoveries without the prolonged sedation or exaggerated depth associated with other agents.

In clinical practice, this makes Alfaxan a highly reliable choice for sighthound anaesthesia, offering the combination of fast metabolism, minimal reliance on compromised enzyme systems, and favourable cardiovascular stability. Together, these features help mitigate the risks associated with both low body fat and reduced cytochrome P450 activity, making it one of the most sighthound-friendly injectable anaesthetics available.

Supporting Evidence

Recent research has strengthened our understanding of why sighthounds process certain anaesthetic drugs so differently. The 2019 Scientific Reports study demonstrated that Greyhounds have markedly reduced CYP2B11 activity at the protein level, despite normal gene expression, meaning the enzyme responsible for clearing many injectable agents is simply less available. This aligns perfectly with the prolonged recoveries and exaggerated drug effects historically seen in these breeds. The study also identified specific genetic haplotypes linked to reduced CYP2B11 expression, confirming that this metabolic difference is inherited rather than incidental. Together, these findings support what clinicians have observed for decades: sighthounds require tailored anaesthetic protocols because their unique pharmacogenomic profile genuinely affects drug clearance. Understanding this allows us to choose agents—such as alfaxalone—that bypass these limitations and provide safer, smoother anaesthetic experiences for these breeds.